Postactivation Potentiation: On The Verge Of New Approach

Performing EOL half squats on the flywheel ergometer.

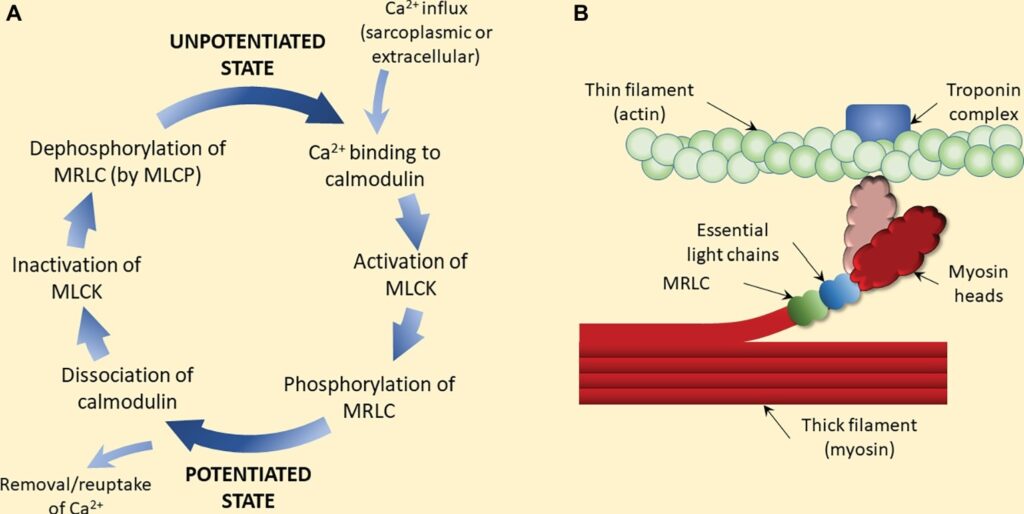

Post-activation potentiation (PAP) is a well-described phenomenon with a short half-life (~28 s) that enhances muscle force production. It is mainly explained by an increase in phosphorylation of myosin light chains in type II muscle fibers. Measurements of muscle twitch force in humans have quantified its effects. In addition, there are also some enhancements in (sometimes maximal) voluntary force production that can be observed several minutes following high-intensity muscle contractions, and these are most pronounced in muscles containing a large proportion of type II fibers. Therefore, we have considered this effect to be a result of PAP.

Proposed mechanism of (classic) post-activation potentiation (PAP).

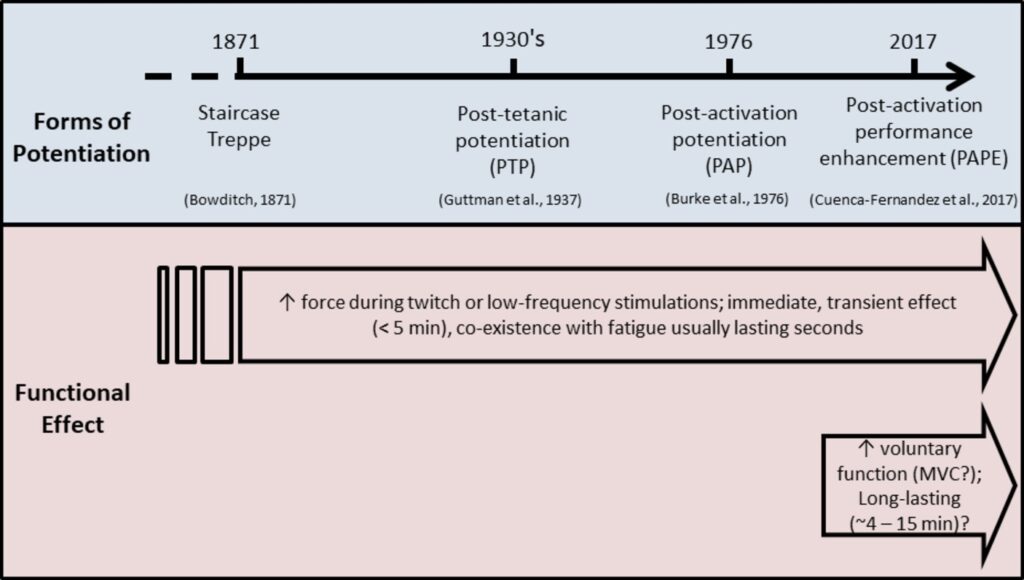

Phosphorylation of the myosin light chains (underlying “classic” PAP) rarely coincides with voluntary force enhancement. As opposed to PAP, changes in muscle temperature, muscle/cellular water contents, and muscle activation may contribute to voluntary force enhancement. To differentiate it from “classic” PAP, this enhanced process is termed post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE). In humans, PAPE is frequently undetectable at a time point when PAP is maximal (or substantial), raising the question of whether PAP can generate PAPE under most conditions in vivo. Additionally, a small amount of evidence is available to support PAP’s practical significance in cases where a thorough, active warm-up has already elevated multiple physiological processes.

History of Potentiation.

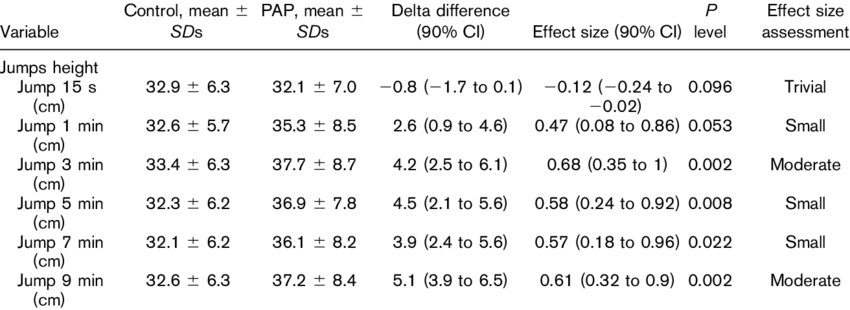

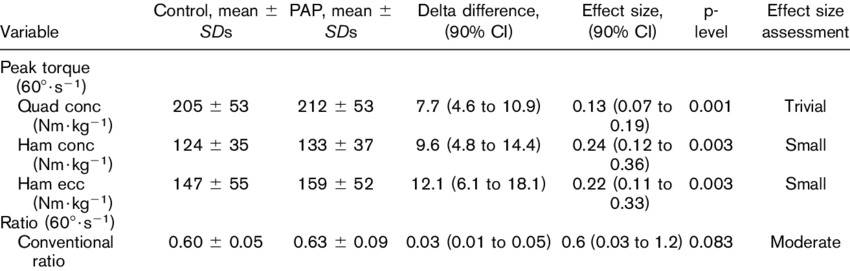

A majority of the postactivation potentiation (PAP) data comes from explosive movements. It has been shown that performing low-volume, heavy resistance training 3-10 minutes before an explosive movement (such as a vertical jump or sprint) improves performance. However, most studies used 85-90% of 1RM load to perform squats or bench press, and results were mixed between positive and neutral outcomes.The purpose of the current study was to determine whether flywheel eccentric overload squats would elicit postactivation potentiation of the vertical jump and isokinetic torque production by the hamstrings and quadriceps muscles.In a randomized, crossover study, eighteen active men (mean + SD, age 20.2 + 1.4 years, body mass 71.6 + 8 kg, and height 178 + 7 cm) participated. A flywheel ergometer was used to perform EOL half squats at maximum power 3 sets per 6 repetitions. Postactivation potentiation using an EOL exercise was compared with a control condition. Countermovement jump height, peak power, impulse, and force were measured 15 seconds, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 minutes after an exercise or control. In addition, isokinetic strength tests were conducted on the quadriceps and hamstrings.Postactivation potentiation vs. control reported a meaningful difference for CMJ height after 3 minutes (effect size [ES] = 0.68, p = 0.002), 5 minutes (ES = 0.58, p = 0.008), 7 minutes (ES = 0.57, p = 0.022), and 9 minutes (ES = 0.61, p = 0.002), peak power after 1 minute (ES = 0.22, p = 0.040), 3 minutes (ES = 0.44, p = 0.009), 5 minutes (ES = 0.40, p = 0.002), 7 minutes (ES = 0.29, p = 0.011), and 9 minutes (ES = 0.30, p = 0.008), as well as quadriceps concentric, hamstrings concentric, and hamstrings eccentric peak torque (ES = 0.13, p = 0.001, ES = 0.24, p = 0.003, and ES = 0.22, p = 003, respectively) after 3-9 minutes of rest.

Summary of control and PAP impulse and force data.

According to the present findings, using an EOL bout during PAP significantly improves the height, peak power, impulse, and peak force during CMJ and isokinetic strength of male athletes’ quadriceps and hamstrings. Moreover, the optimal time window for the PAP was found from 3 to 9 minutes. Thus, this study indicates that eccentric flywheel squats can induce postactivation potentiation of strength and explosive performance.

This study leads to the question, what kind of effects might we expect from applying eccentric overloads to barbell exercise performance? Indeed, we can say that there is much room for improvement and further investigation in the PAP literature, but this study presents a needed step forward. Are you going to immediately apply the new method to your athlete? Depends. If (let’s call it traditional for the sake of conversation) traditional PAP works well, surely you will not change the approach for the main competitions, but during the practice or in the off-season, why not?

The original study can be found by clicking here.

Reference:

Beato M, Stiff A, Coratella G. Effects of postactivation potentiation after an eccentric overload bout on countermovement jump and lower-limb muscle strength. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021 July 1;35(7):1825-32.